The Evolution of the Indonesian Economy

Indonesia, formerly a colony known as the Dutch East Indies, is one of the five biggest economies in Asia and has the 16th-highest GDP in the world. This is a surprising statistic for a young country with barely 100 years of freedom from Dutch rule. After declaring independence in August 1945, the first president, Sukarno, was deposed in an attempted military coup in 1965 where the so-called 30 September Movement (Gerakan 30 September) assassinated six military generals. Many groups within Indonesian society, including paramilitary and religious groups, blamed the Indonesian Communist Party for the formation of the G30S and the coup. These feelings soon exploded into an anti-communist purge. This, in turn, evolved into what could be called a genocide of sorts. Having lost political power in the coup, Sukarno was forced to transfer his power to Suharto, the head of the Indonesian Armed Forces, in 1967. President Suharto then remained in power until the end of the century. He stepped down following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and riots in the country. Despite having gone through several major events in a short period of time, it perseveres. Thus, making it one of Asia’s biggest economies.

The ‘New Order’ of the 20th Century

Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime officially replaced Sukarno’s administration in 1967. It began in the footsteps of the abortive coup and the Western-backed genocide of suspected communist sympathisers and minority groups of 1965-66. The estimated number of victims is 500,000 to 1 million people, although some say it may be millions. The exact death toll is unknown.

The new administration implemented austerity measures to bring down inflation and stabilise the economy. Due to the sudden increase in oil export revenues, Indonesia’s GDP per capita increased more than 500% from 1970 to 1980 during the early years of Suharto’s rule. During the oil crisis of the 1970s, the country had a high economic growth rate of 7%. This lasted for almost 20 years. However, the regime’s main problem was rampant corruption and this facilitated Suharto’s resignation in 1998. It had a weak legal system that could not bring those responsible to accountability efficiently and the seemingly positive economic growth hid the growing corruption of the elites. A Transparency International report came to the conclusion that Suharto was the most corrupt leader of the modern era.

The Asian Financial Crisis and the Fall of Suharto

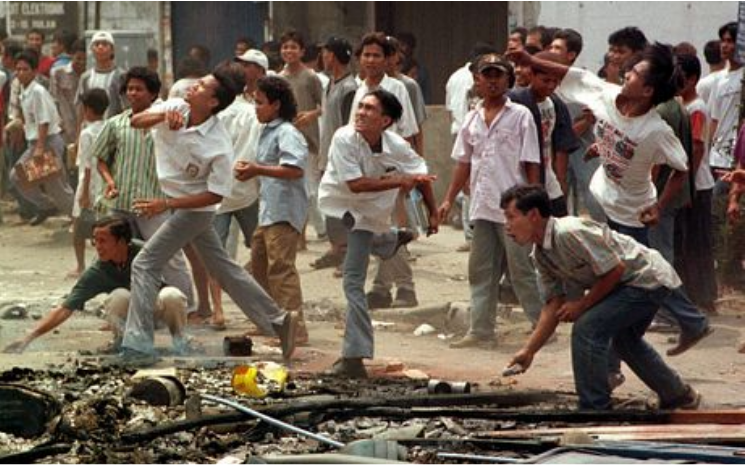

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 was not just an economic crisis. For Indonesia, it was also political. Between 1997 and 1998, Indonesia lost over 13% of its GDP. Even after the implementation of an economic reform programme, the currency remained weak. The regime’s crippling corruption had finally caught up just as many major Asian economies fell. Although the crisis triggered the government’s loss of control, it was not the sole cause. Indonesia was heavily divided - it was and remains Java-centric. Roughly 40% of the population identifies as Javanese in the present day, making it the majority ethnic group of the country. Not only were there cultural divisions, but there were also regional and deeply rooted hierarchical divisions. The tension that had been suppressed by the government started boiling over once the country’s economy was brought to its knees. Ethnic tensions, economic collapse, and general discontent with the authoritarian nature of the government culminated in the 1998 riots of Indonesia. At the end of the century, the country witnessed Suharto’s resignation and the start of Reformation under President B. J. Habibie.

Credit: AP Photo/Charles Dharapak

Onwards and Upwards: Reformasi and Beyond

An era spanning across five presidents and counting, Reformasi continues to this day. Laws regarding government decentralisation and more autonomy for the provinces were passed with the aim of reforming Indonesian society and government. The first free elections since the 1950s were also held under the supervision of an independent commission. The country had a relatively stable period in the early 21st century. It did not experience a time as economically tumultuous as the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 until the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in Indonesia’s first recession in two decades, which saw the real GDP contract by 2.1% in 2020 and an additional 2.5 million people falling into poverty. However, according to a report by the Asian Development Bank released earlier in 2022, Indonesia seems to have rebounded by the end of 2021 with an ‘output higher than in pre-pandemic 2019’. The ADB expects the economy to grow by 5% in 2022 and 5.2% in 2023, as they predict that the next COVID-19 wave will be less severe on economic growth.

As the world enters the post-COVID-19 era, the Indonesian state’s key focuses are on attracting foreign investments and improving its infrastructure to boost general connectivity, especially for e-commerce. Indonesia is also poised to become a giant in the digital economy within its own region, with the Managing Director of Google Indonesia, Randy Yusuf, stating that the country’s digital economy is on track to reach US$130 billion by 2025.

In the span of one century, Indonesia’s economy survived Sukarno’s Guided Democracy era, Suharto’s New Order, and the Asian Financial Crisis. The 21st century, so far, has given the country kinder treatment. Considering the speed of Indonesia’s evolution, it is fair to say that she has taken her position as a leader in Southeast Asia. Those monitoring the country’s growth, such as the aforementioned Asian Development Bank, have faith in her ability to develop quickly and one day be seen as a contender against Western economies. Being a young country born at the tail end of the Second World War, Indonesia understands the need for rapid improvement and has already begun making her mark on the world.

References:

Asian Development Bank, 2022. Indonesia's Economic Growth to Strengthen in 2022, 2023. Asian Development Bank. Available at: https://www.adb.org/news/indonesia-economic-growth-strengthen-2022-2023-adb

BBC, 2004. Suharto tops corruption rankings. BBC. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/3567745.stm

Furusawa, M., 2017. What We Have Seen and Learned 20 Years After the Asian Financial Crisis. International Monetary Fund Blog. Available at: https://blogs.imf.org/2017/07/13/what-we-have-seen-and-learned-20-years-after-the-asian-financial-crisis/

Kwok, Y., 2015. The Memory of Savage Anticommunist Killings Still Haunts Indonesia, 50 Years On. Time. Available at: https://time.com/4055185/indonesia-anticommunist-massacre-holocaust-killings-1965/

Lucas, B., 2009. Helpdesk Research Report: Indonesian Financial Crisis (1997-1998). Governance and Social Development Resource Centre. Available at: https://gsdrc.org/publications/indonesian-financial-crisis-1997-1998/

Sit, D., 2022. Post-Covid Prospects: Indonesia - Interview with Slamet Noegroho, Consul for Economic Affairs of Indonesia in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Trade Development Council Research. Available at: https://research.hktdc.com/en/article/OTU0ODAxNjgw