How do we Break the Chain of Risky Development?

Extreme weather events not only impact nature and humans, but also critical property and infrastructure. The need for a more sustainable and climate resilient built environment is more urgent than ever, yet tens of millions of homes, buildings, and businesses exist in the most climate-disaster prone areas of the country and more continue to be built.

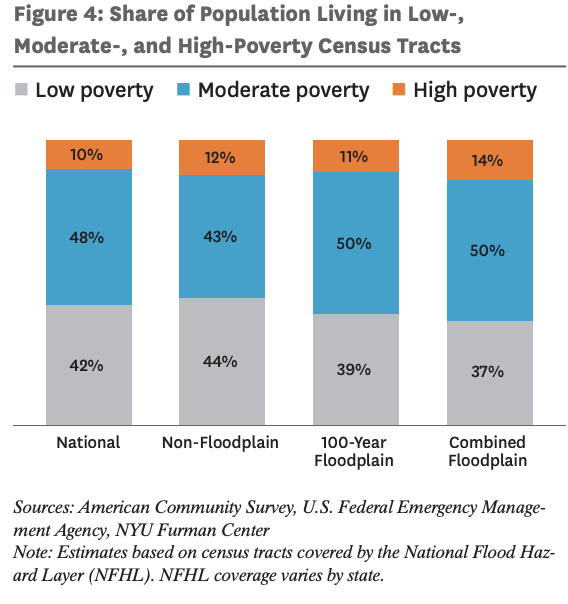

According to a study published in Advancing Earth and Space Science (AGU), 60% of buildings in the United States are in disaster hotspots, despite these areas constituting only 30% of the land mass. Development being concentrated in these disaster-prone areas not only hurts all individuals who reside there, but disproportionately negatively impacts those who are the least financially prepared to deal with the consequences of extreme weather events–– children, the elderly, and those in poverty. What explains the continued decisions to live and build in these climate-risky areas and what policy changes can be implemented to disincentivize this climate-risky development?

Human behavior, culture and poverty, and lack of transparency.

One of the largest obstacles to proactively addressing the climate change crisis stems from the fact that humans have a tendency to overvalue immediate rewards and overlook potential future consequences: a trend described by behavioral economists as present bias. This, coupled with the fact that risk is oftentimes not disclosed to home buyers or renters in a transparent manner, leaves individuals unexpected and unprepared to deal with the consequences of extreme weather events.

Along with these factors, cultural norms also impact the ability of individuals to protect themselves from disasters. Disaster warnings are commonly issued in English, leaving non-English speaking populations less likely to understand and prioritize them, ultimately limiting their ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters. A similar trend is seen amongst those who live in poverty as they suffer the greatest losses from disasters and have the least access to public and private recovery assets. Both of these factors contribute to vulnerability which, in the disaster context, is defined as “a person’s or group’s capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” (Blaikie et al., 1994, p. 9). Vulnerability is influenced by race, gender, social class, and other socioeconomic factors.

Risk-sharing.

Financial costs from extreme weather events are spread across multiple actors, resulting in individuals, companies, and public agencies facing asymmetric consequences in face of extreme weather events. This creates a moral-hazard problem in which there is little incentive for actors to change their risky development patterns, ultimately gridlocking reform.

With more than half of U.S. mortgage loans being securitized by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the federal government is responsible for outstanding mortgage debt in disaster prone areas. The Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 and the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994 mandated the purchase of flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) for all Federally backed mortgages on buildings and homes located in Special Flood Hazard Areas. many argue that the United States’ primary flood insurer, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), actually incentivizes risky development through its subsidized insurance structure, ultimately leading to more development in flood prone areas.

Along with this, the program has seen low participation rates, which is worrisome as insurance payments are the programs intended principal source of income, leaving the program operating in debt since 2005. Also, the NFIP is not very transparent; oftentimes leaving buyers and renters in the dark. Lastly, the program fails to factor in other climate risks when securitizing loans, which can be argued to incentivize homeowners (or at the very least not disincentivize them) to purchase in those areas.

Political incentives.

Compounding all of these issues discussed above, is the fact that in today’s political environment, elected officials are strictly motivated by actions that will help them get reelected. This rise of permanent campaigning and growing polarization on hot button issues has been accompanied by a rise in position-taking––oftentimes without actual legislative action. Policymakers have become more attentive and responsive to public opinion and choose to engage with issues that are beneficial for their reelection. The NFIP and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) (its parent agency) came under harsh public criticism for its response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, leading lawmakers to reevaluate their public positions on disaster management and learn more about the failures of the NFIP. However, lawmakers failed to keep the public informed, leading the rise in premiums as a result of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act (an NFIP reform) to be misunderstood and ill-received by the public. This, coupled with the devastation of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, has made reform very unpopular amongst the general public, ultimately leaving policy makers stuck in a standstill. Despite the increasing severity and frequency of extreme weather events, politicians continue to prioritize their reelection agendas, failing to make substantial and sustained policy changes.

Suggestions

Political Coordination & Increased R&D

Disincentivizing development in climate risky areas requires better coordination amongst political instruments, coupled with increased research and development (R&D) to promote more holistic reform of the institutions and programs tasked with preparing for and responding to climate disasters. This type of multifaceted response would help to manage land and climate risk, advance food security, and help alleviate equity concerns. Flood zone mapping, financial incentives for people who live in special hazard flood areas (SHFA), building restrictions, and improved insurance are flood resilience policies that would be both effective and mutually reinforcing. Also, investment in research would lead to a greater accessibility amongst the general public of information regarding disaster hotspots and future projected costs, making it both harder and less appealing (election-wise) for policymakers to develop in these risky areas. Additionally, increased R&D would help improve catastrophe models that assess damages and costs associated with different natural disasters. Insurance and securitization companies can utilize these models to determine premiums that accurately reflect risk. With higher premium costs serving as signals for increased risk, individuals would be able to make more well informed decisions about where and how to build. While it may not completely disincentivize development in these areas, the transparency allows developers and owners to factor these climate risks into their development plans––possibly encouraging more resilient and precautionary measures.

Improving the National Flood Insurance Program

The NFIP is in need of holistic reform. A comprehensive reform plan from FEMA, increased engagement with private insurance companies, and efforts from policy makers and key actors to better explain the intricacies of the program to the general public could be a great start. Additionally, the NFIP has failed to regularly update its flood maps with modern information, focusing on historical flood data when deciding premiums. The NFIP should shift its focus to take future risk projections into account while expanding its scope of focus to areas that are outside of the 100-year floodplain boundary. Lastly, low-interest loans can be instituted to help homeowners undertake flood-mitigation projects, well-enforced building codes can encourage the adoption of cost-effective loss reduction measures, and vouchers can serve as financial assistance for low-income families to purchase insurance and invest in mitigation measures.

References:

Donner, W., & Rodríguez, H. (n.d.). Disaster risk and vulnerability: The role and impact of population and society. PRB. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://www.prb.org/resources/disaster-risk/

Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. A. (2004). Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards, 32(1), 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:nhaz.0000026792.76181.d9

Hurlbert, M., & Krishnaswamy, J. (n.d.). Chapter 7 : Risk Management and decision making in ... - IPCC. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/chapter-7/

Iglesias, V., Braswell, A. E., Rossi, M. W., Joseph, M. B., McShane, C., Cattau, M., Koontz, M. J., McGlinchy, J., Nagy, R. C., Balch, J., Leyk, S., & Travis, W. R. (2021). Risky development: Increasing exposure to natural hazards in the United States. Earth's Future, 9(7). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020ef001795

Kunreuther, H. (2018). Improving the National Flood Insurance Program. Behavioural Public Policy, 5(3), 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.26

NYU, F. C. (n.d.). Population in the U.S. floodplains - furman center. Retrieved June 7, 2022, from https://furmancenter.org/files/Floodplain_PopulationBrief_12DEC2017.pdf

Schuetz, J. (2022, April 11). Home mortgage and insurance systems encourage development in climate-risky places, and we all pay the price. Brookings. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2022/03/09/home-mortgage-and-insurance-systems-encourage-development-in-climate-risky-places-and-we-all-pay-the-price/

Tier, M. (n.d.). Overcoming contemporary reform failure of the National Flood Insurance Program to accelerate just climate transitions | journal of public and international affairs. Princeton University. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://jpia.princeton.edu/news/overcoming-contemporary-reform-failure-national-flood-insurance-program-accelerate-just-climate